The Purslane Passport

If “rewilding” sounds like it involves going off into the jungle to commune with trees, leaving all worldly relationships behind, nothing could be further from the truth. Through the process of learning about India’s wonderful, wild, edible, weeds I’ve made so many new connections with fellow foragers. Nothing illustrates this better than my encounters with purslane or Portulaca oleracea, an uncultivated green found across the Earth’s diverse climatic conditions, and my passport into a whole new culinary world. Coincidentally, portulaca means “little door” in Latin (a reference to the portal-like seed pods), while oleracea means “edible”.

The ancient Romans and Greeks ate purslane, and the plant found a place in the diet, medicine, and poetry of ancient Egypt too. American herbalist Euell Gibbons, sometimes called “the father of modern foraging,” referred to purslane as “India’s gift to the world,” believing that it originated in my home country.

While its actual origins are unclear, purslane was certainly enjoyed by India’s most famous leader, Mahatma Gandhi, who wrote about trying the leaf, foraged by an associate, during a period when he lived entirely on uncooked foods. Purslane, he wrote in his journal Harijan, “agreed with me.”

A carpet-like plant that thrives in moist soil, purslane grows tenaciously in hot climates because of its ability to store huge amounts of water in its leaves. That’s also why it grows so abundantly in sidewalk cracks, amidst urban heat and pollution. The next time you step out, look closely at the edges of walkways to see if you can spot the plant. Odds are, you have seen purslane sprouting up wherever you live.

Finding Purslane

I first encountered this humble, uncultivated weed a decade ago, in the dry farmland of Telangana in southeastern India. It was a summer afternoon, and as my colleague Satyamma foraged under the scorching sun, she explained that gangabai kura, as purslane is called in this region, is traditionally eaten during the hot months to help cool the body.

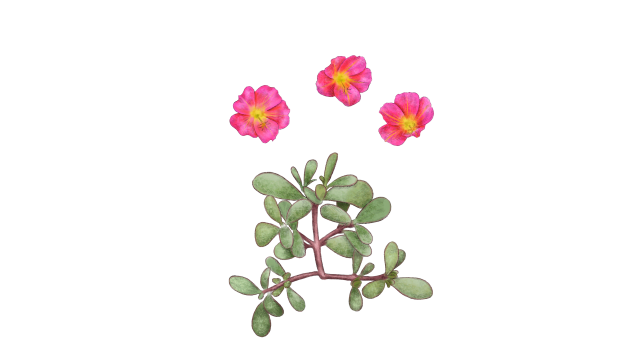

I helped Satyamma pluck from the creeper with smooth, ovate, leaves, noting the pink-tinged stems and tiny yellow flowers with just two sepals. She cooked the purslane into a delicious dal, to be eaten along with jonna roti, a millet-based flatbread. I noticed how the succulent leaves melted right into the lentils, giving the dish a slightly tangy flavor.

As a novice forager out on my own, I initially had trouble distinguishing between the varieties of the purslane family, some of which are easily confused with weedy common purslane. There is the smaller, also edible Portulaca umbraticola (wingpod purslane) as well as the ornamental Portulaca grandiflora (moss rose), which is non-palatable. It was through my interactions with other plant enthusiasts and the Forgotten Greens workshops I run, that I learned how to differentiate between them. In the process, purslane helped me knit together a community that is spread as far and wide as the plant itself.

Wild purslane grows all over India, but it can also be found occasionally in the markets of Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu — where it is respectively called ghol bhaji, luni bhaji, or kodi parrupu keerai. A few years ago, my mother-in-law brought a bag full of kodi parrupu keerai, which translates to “purslane that climbs” from a wholesale market in Chennai. Seeing my excitement, she gave me a small handful to propagate on my terrace garden, instructing me to “Just drop these root nodes in the pot and water it well.”

Once I knew it was available, I was surprised to find the tiny succulent leaves, complete with their roots, in a few of Chennai’s vegetable shops. My mother-in-law cooked it with dal, enthusiastically extolling its nutritious properties. As a part of the daily food scene, paruppu keerai is no longer a completely uncultivated green. I love cooking it with meat, especially chicken, as well as in dal. The greens add a unique, earthy tang, as well as their own health benefits, including being one of the highest plant-based sources of omega-3 fatty acids.

A Harbinger and a Gift

Beyond my mother-in-law in Chennai and Satyamma in Telangana, purslane brought me to other foragers and other local traditions. For example, Nandita Amin, an avid forager from Vadodara, Gujarat, introduced me to the Gujarati dish luni ni bhaji na muthiya, made specifically from wild purslane during one of our “Rewild Your Life” workshops.

Then Fouziya Tehzeeb explained how the appearance of purslane heralds the beginning of spring in Kashmir. “There’s nobody to tend to it, but it grows in all warm-hot weather conditions, with or without water,” she said, marvelling at how purslane “endures everything yet it chooses to stay tender. It melts away the moment you put it in the cooking pot.” Tehzeeb recalled how her grandmother would go out with her friends “with their phutte [wicker baskets] and small knives” to dig out nunnar, as purslane is called in Kashmiri.

During a conversation about how to propagate wild edibles in our garden spaces, another fellow forager shared a hack to growing purslane. The plant has tiny black seeds, which slough off in the water used to clean the plant. Simply pour this water into your garden, and the seeds will be deposited along with it. If you keep your pots wild enough, you will likely find purslane growing there with even less effort.

As the world faces alarming upward shifts in base temperature, I see purslane as one of the answers to the challenges of our ever changing foodscapes. As we move toward water-scarce, highly urbanized environments, purslane’s resilience, ability to conserve large amounts of water, and its grit to thrive in the most unexpected places, is a small sliver of hope.

Key Takeaways

- Purslane offers vitamins, iron, and calcium.

- It has high levels of omega-3 fatty acid.

- It offers hope for a climate-challenged planet.