Q&A with Charmaine O’ Brien

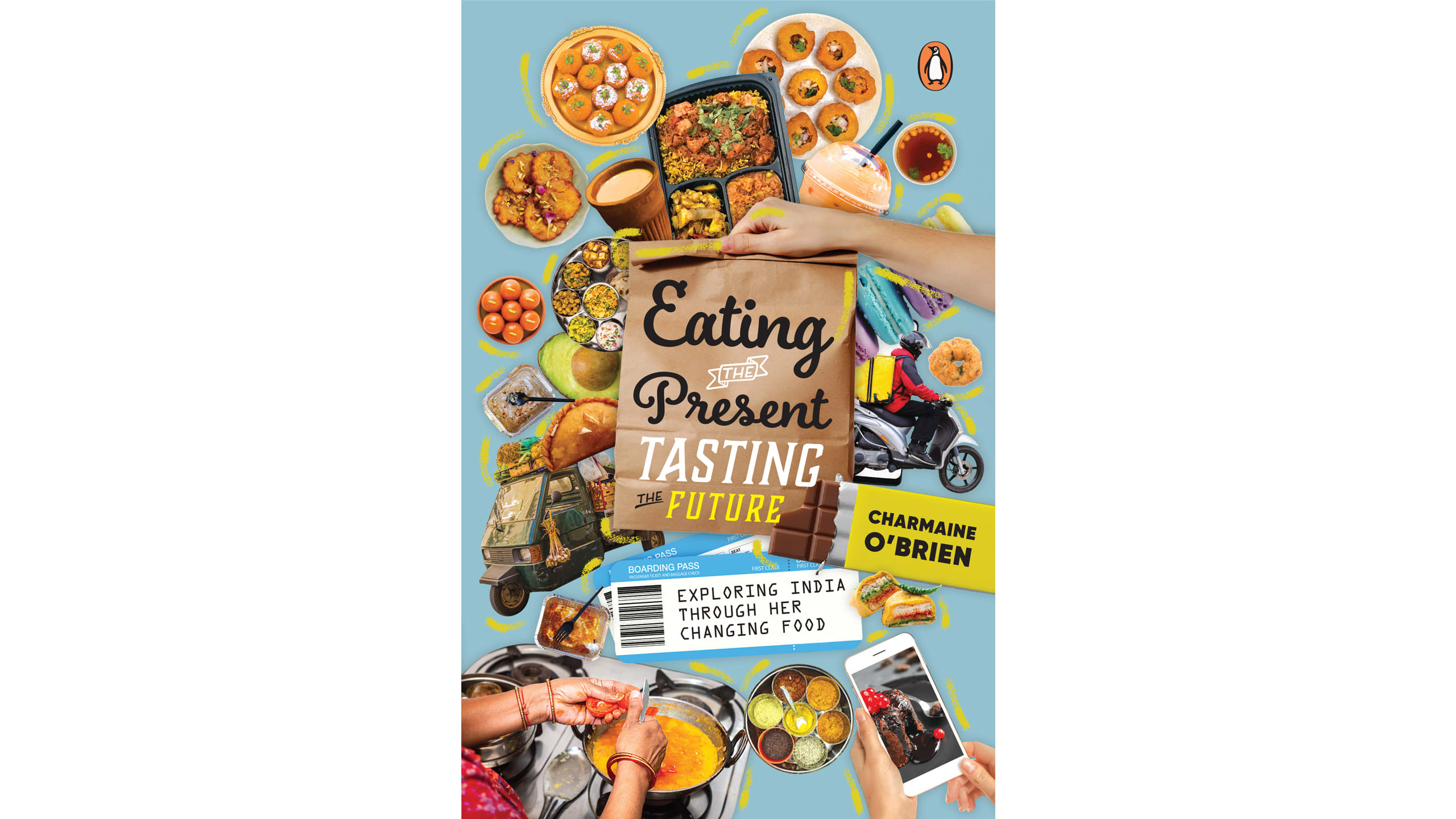

The story of how a Melbourne transplant in Delhi, perplexed by food stereotypes (and bit by a nasty tummy bug), found the true essence of Indian cuisine in a tiny eatery in south India serving nourishing food sets the tone of Charmaine O’ Brien’s latest book Eating the Present, Tasting the Future. The book is an important record of India’s cuisines, their influences on global food, and vice versa. O’Brien highlights the rich variety of regional cuisines, the healthy habits around domestic cookery led by women in India, and the emergence of restaurants and food trends voiced by experts in India.

Early on O’Brien would be found hanging around in her mother’s kitchen and devouring her mother's cookbooks. Today O'Brien's insatiable love for food has propelled her across continents, inspiring her many books. Her food interests are varied, and she is the author of Lonely Planet’s World Food: New Orleans, Flavours of Melbourne: A Culinary Biography, The Penguin Food Guide to India, and Flavours of Delhi, Recipes from an Urban Village: A Cookbook from Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti. Following Eating the Present, she is working on her next cookbook exploring her Anglo-Celtic culinary heritage.

Outside of her books, O’Brien teaches cooking classes and offers culinary workshops, curating food trails and cooking for small groups. She aims is to nudge people to build a holistic relationship with food and understand the impact and intersection of culture, economics, and politics on our food decisions.

Roundglass Food: You talk about a strong nexus between wellness and domestic food. What are the reasons for it?

Charmaine O’ Brien: Historically, there was always a nexus between wellness and food because for most of human history food was the only “medicine” available to people, and most people ate food prepared in the domestic sphere so domestic food was the source of wellness. Up until the early 20th century it was common for British/Australian/American (Anglosphere) cookbooks to have a section on “invalid cookery,” which gave recipes for dishes and drinks to help a family member recover from illness.

As our knowledge of medicine turned sophisticated resulting in the greater availability of pharmaceutical drugs, hospitals, surgeries, and educated nursing, looking after health moved out of the home into the “medical” world — which can mean better and more effective treatments, but it also means paying for healthcare. Achieving “health” or wellness in the contemporary world has become a consumer business. The contemporary concept of “wellness” is very product-centered, i.e., you can buy wellness through consumer items such as special foods and drinks, vitamins, and scented candles.

I think food has remained a key source of wellness in India in part because of economics, i.e., people did not have the means to afford, or perhaps even have access to, consumer medicines or allopathic medical services so they had to manage health at home through food and this has ingrained this approach in India.

It also aligns with India’s traditional Ayurvedic system of healthcare that prescribes food as medicine. Again, this is an ancient system and food, including spices and herbs, was the only thing available as medicine/health treatment. Another aspect is the impact of the caste system, whereby food could be ritually polluted if touched by a lower caste person, or foods that were not caste appropriate were used. Therefore, it was vital to maintain caste purity, or caste “health” to ensure that food was cooked in the “safe” environment, that is the domestic home.

All in all, food cooked in one’s home by someone you trusted to look after your wellbeing (female relative, a caste-appropriate cook) became embedded as key to maintaining bodily, social, and spiritual wellness in India. As their economic prosperity has increased for many Indians over the past few decades, “wellness” has likewise become commercialized. Over time this is likely to result in less care being taken in the kitchen to ensure family health and more consumption of medicines, vitamins, commercial “health” foods (i.e., prepared in a commercial premise) instead: demonstrated in the ever-rising valuations of the health and wellness/diet industries in India.

RG: Since most of the domestic cooking in India is done by women, what are the wellbeing influences and health and nutritional factors that Indian women are responsible for?

COB: I am not sure I want to say that women are “responsible” for maintaining anybody’s wellbeing, rather it is an expectation in many families that they do so. (There is no reason a man could not do the family cooking and take on this “responsibility” as such.) I think Indian families expect that whoever is doing the domestic cooking, which is most often a woman, will plan and prepare meals that are “good” for them and suit their material, cultural, social, and religious/caste needs.

In preparing meals for her family, a woman, or a man, can teach their children to eat well, according to material circumstances and alignment with cultural, social, and religious/caste expectations. If people are not cooking at home as much and ordering food in a lot or using a lot of convenience foods, they are perhaps reneging on the opportunity to teach their children how to value the labor, effort, and thought that needs to go into cooking and consuming a good diet.

If children don’t see cooking in their home and perhaps hear discussion about what is to be eaten and what the preparation and ritual of particular dishes mean for bodily and culture wellness, then they might be more likely to eat more convenience food/pre-prepared food into the future because they have no idea how to do otherwise. However, this should not fall entirely to the woman: both parents can take an active role in creating a good eating example in their home.

RG: A significant population in modern metropolitan India are either obsessing over global superfoods like quinoa, avocado and olive oil, or asparagus while others are raging over the popularity of moringa, jackfruit and turmeric as culinary appropriation by the West. What’s wrong here?

COB: The most influential factors affecting people’s food choices in the contemporary food sphere are branding, packaging, and marketing; social media also has a significant influence. Ultimately it is about economics. Take millet for example, not that many years ago it was “poor man’s food” now it is a so-called “superfood.” What has changed? Millet itself has not changed but the words used to describe it have, and once you call a food “super” or “free from” or tie it to a particular diet you can charge a higher price for it.

The term superfood is actually a marketing term; there is no agreed definition for it nor any conclusive science to support this concept. Undoubtedly any food labeled as a superfood will be a wholesome nutritious food, just like any unadulterated unprocessed food. All foods have nutritional benefits these are just different for different foods. Because “wellness” branding and labelling allows for a higher price such foods these become classed, i.e., the hefty cost turns them into status symbols.

We are also now living in societies where “healthism” reigns, that the view that individuals are entirely responsible for their health and that one’s wellbeing is totally under their control (disregarding any genetic or environmental influences), therefore if you are ill or unwell it is your fault because you have the wrong diet or you are not consuming [insert latest exclusionary diet or superfood or fermented foods]. These diet styles and wellness food products hold out the promise that you can avoid illness, for example “prevent cancer,” or even cure cancer, by consuming enough of them.

Social media feeds into this as well as people seek to influence others to consume certain food and drinks to improve their “wellness.” While well-off urbanites around the world are enjoying their highly-priced quinoa salads, coconut or almond lattes, acai bowls, and avocado on toast, the places these foods are grown to support this demand are suffering negative environmental impacts (coconuts, quinoa, acai) and/or taking up too much water (almonds and avocados).

It is likely something similar will happen with millets in India. Millets are a valuable and important indigenous food in India and their cultivation is less harmful for the environment, but as demand increases and people are willing to pay more for this newly crowned “superfood,” farming millet will inevitably become intensified with subsequent consequences.

Makhana is another example. This food, used for centuries in India especially during periods of vrat, has recently been crowned with the label of “superfood” and I write in my book how I found its consumption promoted as preventing “fine lines and wrinkles.” This claim is utter nonsense, but it will inspire consumers to pay an inflated price for it as they seek to “anti-age,” which “wellness” is also used as a subterfuge for (our fear of the physical changes of aging).

I recently noticed macadamia nuts promoted as a superfood in the most upmarket grocery store in Delhi. Macadamia nuts are native to Australia (although commercialized in Hawaii) and are not promoted as a superfood here because they are not “exotic” in Australia, but they are in India. Macadamia nuts have a high oil content and score high on some nutrients but so do peanuts. If you look up a comparison of these nuts not only are these on a par for their nutrient value, but you might also conclude that peanuts are a better choice. Yet, peanuts have not been pronounced as a superfood, probably because but these are a common everyday food across India, so it is unlikely people be willing to pay more for them.

Being “exotic” is one of the key features of a superfood, which means many of these are often shipped in from other parts of the world into places to be bought by consumers who already have abundant food choices and more than sufficient to eat. Do Indians really need to eat avocados shipped in from places such as Australia and Guatemala? Will their wellbeing suffer if they don’t eat avocados?

So, what is wrong here is that we are swayed by persuasive words, attractive packaging, and attractive “influencers” gushing about being “well” and pointing to the consumption of various food and food products as key to wellbeing. The British initially came to India to gain access to spices as these were expensive and therefore highly desirable, the “superfood” of the medieval world, and look how that turned out! Unfortunately, status foods are a constant social fact.

I think one of the best things you can do for your “wellbeing” from both a bodily and psychological perspective is to limit your time on social media. If you are “influenced” by celebrities/wealthy people to take up their recommendations on wellness, really think about that person’s reality, and why you believe them. Is it because they are famous, rich, thin, attractive? Think about the considerable resources — cooks, personal trainers, the money for surgical procedures, skin treatments — they have to keep themselves “well,” which more often means being slim and youthful looking. I wouldn’t trust any wellbeing or dietary recommendation just because a celebrity or attractive influencer endorses it. I also recommend listening to a podcast called Maintenance Phase if you want to learn more about wellness grifters and arm yourself against their predations.

RG: In your experience which region can be called the equivalent of the Mediterranean type of cuisine in India?

COB: I can’t think of a region that is a direct correlation. However, I think India’s regional food cultures generally equate with the Mediterranean Diet (MD) in that these are tied to the geography and climate of the places they belong to. The MD incorporates olive oil because olives grow abundantly in that soil and climate. A point to note here is that olive oil is not the only “good” oil or the best oil — the fact that you might think so is largely due to marketing. India produces plenty of her own oils that are excellent and of their place: sesame oil, coconut oil, mustard seed oil are examples.

The MD diet is largely based on vegetables and whole grains, with small amounts of meats, as are most of India’s regional cuisines. The MD incorporates fish because the Mediterranean has a lot of coastlines, just as India’s coastal communities do, along with other regions with access to waterways (Gujarat being an exception to this).

A traditional MD is also one that is prepared in the domestic kitchen, just like India’s regional cuisines. There is no need for Indians to run after the MD diet, and buy expensive food products associated with it, just have a look around you. Think about any Indian regional home cooking most of the time there is not a lot of oil or fat or used in everyday cooking. Some is used, but in my experience Indian home food is light and fresh. Yes, there might be a fried element and/or a meat dish but it is not excessive. Celebratory meals tend to be an exception, as these are in any food culture.

The MD is one that includes a wide variety of different foods; think of a typical home cooked Indian meal there is always a lot of food variety: a dal, a couple of vegetable dishes (at least), perhaps a non-veg dish, wholewheat bread or rice, curd, pickles, and other condiments. Indians can easily look in their own regions/food cultures for ideas if they think they need to improve their eating for health reasons. You don’t need to import an external dietary pattern.

RG: What are the possible fallouts of putting a “health halo” or labels around foods like gluten-free or organic that you have observed in India?

COB: Disrupting traditional food systems with subsequent environmental impact. The world-wide craze for quinoa and acai, both nutritious foods, have disrupted the foodways of the communities that have been cultivating these foods for their own use for many hundreds of years. This is causing both environmental degradation in order to create supply to fill the external demand. Social disruption can also occur in these communities due to the change in demand for their traditional foods. I expect this will happen with millets in India (but I could be wrong).

Health halos around food can also cause people to overeat these or cut out other perfectly good foods such that there might be a negative impact on their wellbeing, certainly there will be on their bank balance! Ultimately, the people who can afford foods with a health halo around them are those with plenty of choices available to them and who are actually well nourished. The fallout for them is being unduly concerned about their health, aka the ‘worried well’.

RG: The nutrition-health-diet space is always shifting. Foods like oils and fats or eggs or diets like Atkins, Keto, the DASH diet etc., are celebrated or rejected at different points of time. How is one to make sense of this to follow a healthy approach to food?

COB: One of the most important things is to keep in mind that there is a “Wellness” industry worth trillions of dollars. I think it is important to understand that there is a huge commercial imperative in trying to influence us to follow certain diets and incorporate certain foods. There is nothing wrong with wanting to sell us food products but just be aware of this. If you want to believe claims that any particular food is superior for your health than another do your own research on this. You will often find there is no good evidence to support the claim.

Also, many commercial “health” foods are actually highly processed. Just because a commercial biscuit is gluten-free it doesn’t make it any “healthier” than regular biscuits. It just means it does not contain gluten.

Most importantly though, get into the kitchen and cook most of what you eat from scratch from whole seasonal foods that are also as local as possible. If you don’t feel like cooking sometimes then go out and eat something from a good food vendor. Most importantly, enjoy what you eat, but also accept that if you want to eat well you have to make an effort: value cooking (learn to cook if you don’t know how to) and even cleaning up afterwards (being active!).

RG: How is it India with its legacy of culinary wellbeing is wracked with diabetes and other lifestyle diseases?

COB: I think western influence has had considerable impact on changing food in India over the past two decades, especially through technology (television/OTT platforms, social media) but I am not sure it is to blame for India’s diabetes problem — I think Indians have managed to grow that on their own account! Increasing affluence aligned with greater availability and consumption of processed foods (people have the discretionary income available to purchase these) combined with lack of physical activity are usually culprits in lifestyle diseases for urban Indians. Plenty of Indian companies are making processed/junk/fast/sugar laden foods.

I imagine there are also environmental and psychological factors involved. One of the things I have aimed to do in the book was to place the changes I have observed in India’s foodways over the past three decades into a broader framework of universal changes that happen with food in any society with increased prosperity and concurrent and interrelated technological change and I can say that Indian’s are following a historic pattern. I think if anything is to blame it is the human condition.

I think wealthy societies around the world (not just westerners) are participating in a new type of colonialism in extracting so-called “superfoods” from poorer communities around the globe to “feed” their pursuit of healthism.

RG: You call India a culinary superpower. What will her global impact be in the nutrition and food space?

COB: The diversity of food in India is arguably incomparable, yet non-Indians are only now coming to understand that Indian food is not just “curry” and will want to know more. This will lead to interest and exploration, which will see more Indian dishes and food approaches appear in restaurants and cookery books internationally.

One example I have noticed recently is the golguppa/pani puri appearing outside of India stuffed with things like hummus and avocado. The food industry in any country is always looking for new foods as it thrives on novelty and India has plenty of “new” dishes and foods for non-Indians to “discover.”

India also has the world’s most advanced vegetarian cuisine and plenty of “naturally” vegan dishes and as these eating concepts become more prevalent amongst the world’s most privileged, India will be a source of new ideas and inspiration. Chefs, food writers, food producers and culinary tourists will be coming to India in greater numbers to look for new food ideas and food experiences and much of this will be promoted in the “wellness” sphere. “Wellness” is the new “gourmet” when it comes to food. The appropriation of Indian health concepts into commerciality is only going to grow.

Key Takeaways

- O' Brien on the nutritional variety of Indian cuisine.

- The impact of Western food choices on India.

- The celebration of India’s healthy cooking practices.