Q&A with Colleen Taylor Sen

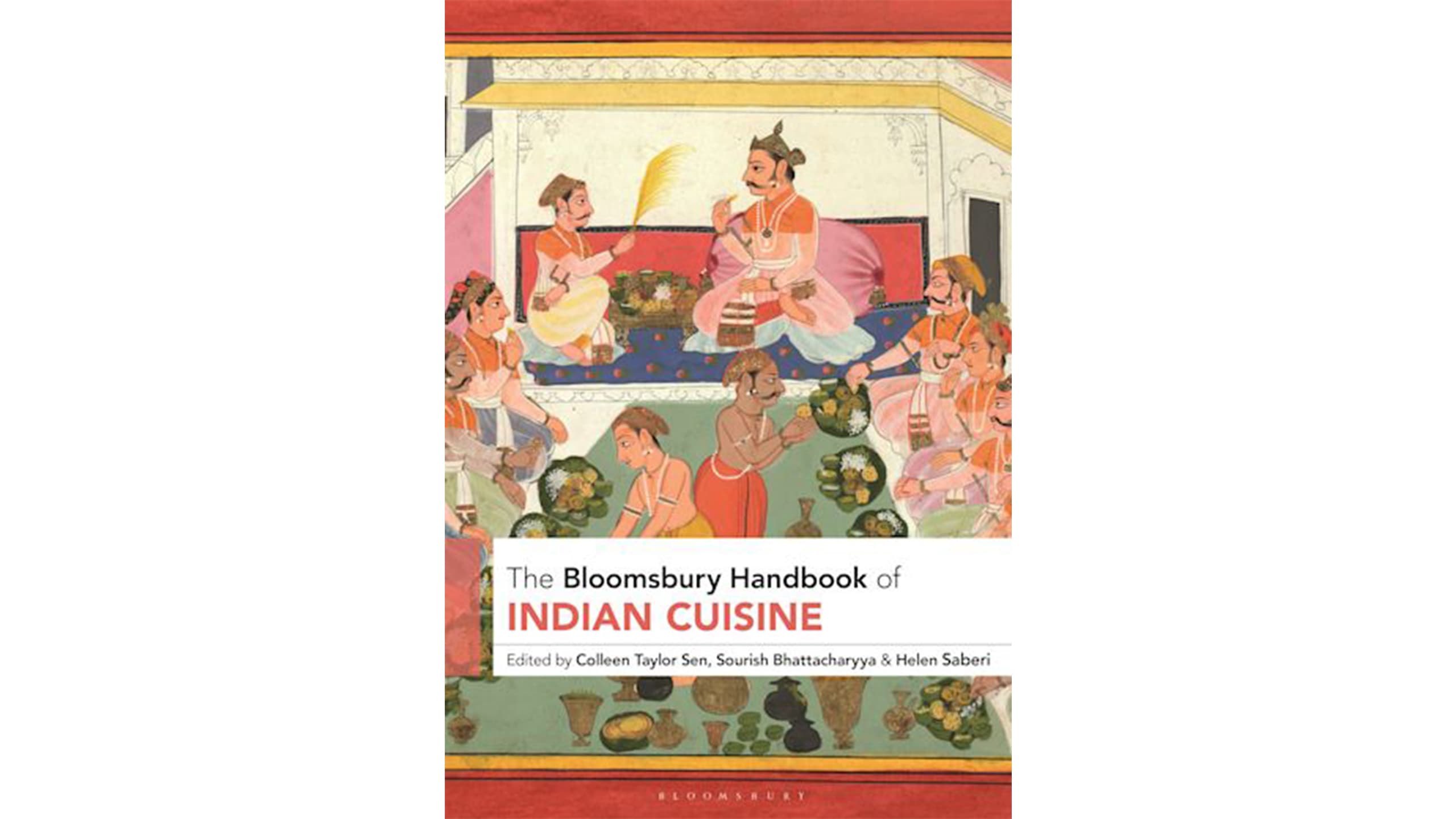

Culinary scholar and food historian Collen Taylor Sen’s deep exploration of Indian cuisine has yielded seven books on the subject, winning awards, and critical acclaim along the way. The latest addition is The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine, for which Sen is one of the editors. The Handbook is first of its kind that encapsulates the wide variety of regional cuisines, restaurants and their culinary inventions, iconic cookbook authors, the culinary imprints of dynasties and rulers of ancient India, the history of ingredients, and related recipes and properties that distinguish them as quintessentially Indian.

A Canadian transplant from Toronto to Chicago, Sen holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University, and her academic rigor is evident in her food books backed by thorough research with lively historical, political, and social insights. Sen’s strong connections with Indian food were forged after her marriage to Ashish Sen and she backed her curiosity and interest with analysis of the country’s varied culinary delicacies, ingredients, and traditions.

On a lucky day you might find her on one of Chicago’s neighborhoods taking people on Indian food tours to sample its regional diversity beyond the bland commodification for Western palates.

Roundglass Food: What is the impact of Indian cuisine on the global foodscape?

Colleen Taylor Sen: While in the UK Indian cuisine has been integrated into British cuisine on all levels (both neighborhood joints and Michelin-starred restaurants), this isn’t the case in the US where Indian food ranks behind Chinese, Thai, and Mexican cuisines in popularity. The items most people order are saag paneer, tandoori chicken/chicken tikka masala and samosas.

Many non-Desis are afraid to venture outside this limited range although I think they would like to — they just need guidance. Recently I organized tours of the Indian shopping district for the local historical society that ended in lunch in a Hyderabadi restaurant. On the menu were halim, seekh kebab, dum aloo, biryani, paratha and Qubani ka meetha. Although many of these dishes were unfamiliar, people loved them, especially the halim. Recently a restaurant opened in Chicago serving authentic Kerala food and it has been very successful, showing the market is there. Restaurant owners need to play a more active role in introducing non-Desi diners to the wonderful variety of Indian dishes.

RG: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine is a mammoth endeavor, and the first of this century after Achaya’s. What do you want readers familiar and not familiar with Indian food to take away from this compendium?

CTS: The Handbook was originally published for a Western audience and intended as a standard reference work. For these readers who may not be familiar with Indian food, the Handbook contains entries on such fundamentals as basic ingredients, spices, major dishes, religious practices, the cuisines of all the Indian states and major cities and communities (written by local experts) and important historical figures. To add a little spice to the mixture, we also added profiles of less well-known figures and institutions that played a role in the development of Indian food.

The Handbook was not intended as a restaurant guide or a survey of contemporary Indian cuisine. We see it as the next iteration in the ongoing expansion of knowledge about Indian food. There’s no way this vast diverse region could be covered in a single volume or indeed, a hundred volumes. Our hope is that every state, every city will one day have its own Handbook.

RG: According to the TBHIC (The Bloomsbury Handbook), India’s first written recipes were by Ayurvedic physicians and “in India food and medicine were virtually interchangeable.” What were the reasons for the close connections between food, health, and wellbeing in ancient India?

CTS: Before the advent of allopathic medicine, food and plants were the main source of healing for many civilizations. By trial and error, they discovered cures for many common ailments. People forget how many modern cures came from Ayurveda: Rauwolfia for hypertension, chaulmoogra oil for leprosy, turmeric for infections.

RG: TBHIC has a compilation of many Indian cookbook writers from 11th century to contemporary times. What sets them apart from cookbook authors from other cultures?

CTS: In India, as in the Middle East, China, Europe and other civilizations, early cookbooks were also medical texts where recipes were given to cure ailments. In fact, the world recipe/receipt meant both prescription and recipe until the 18th century when the second meaning prevailed.

RG: What did you learn from your research on Emperor Asoka and the legacy of ancient India’s greatest empire on Buddhism and its impact on food choices?

CTS: Although Ashoka was a Buddhist, his message of Dhamma which he promulgated in inscriptions throughout his empire was not a Buddhist message but ethical and moral guidelines applicable to adherents of all religions. Several of these inscriptions advocate abstention from killing and harming animals.

In one inscription, Ashoka talks about his personal commitment, proclaiming that he has ended the killing of animals for meat at his own court except for two peacocks and a deer which will also stop. This indicates that he himself adopted a vegetarian diet. Ashoka also set up hospitals and pharmacies for animals—the first in the world. This and his advocation of ahimsa, may have been borrowed from the Jains, and certainly won him popularity among the followers of Jainism, Buddhism, and the many other sects that existed at the time.

RG: Do ancient Indian medicine systems and food habits still hold good?

CTS: Ayurveda’s holistic approach to health and disease has become popular in the West. Major hospitals have departments of Alternative Medicine, including Ayurveda, and many people regularly take turmeric and bitter melon for their health-giving properties.

RG: Fasting is the new global health and diet mantra. Could you share insights from your book Feasts and Fasts on the unique features of India’s ancient fasting traditions?

CTS: Fasting is a practice common to all religions. It can take many different forms ranging from total abstention from food to eating only certain dishes, or only at certain times. I’m intrigued by those Hindu fasts that involves a category of food called phalahar. Food materials are divided into two categories: anna, which are harvested with the help of special equipment, such as rice, wheat, barley, and lentils, and phala, those that grow without special cultivation, e.g., wild grains, vegetables, fruits, certain roots and tubers, leaves, and flowers.

During these fasts, breads and snacks are made of dried water chestnut flour or lotus seed flour instead of wheat and other grains. This type of food is both healthy, especially for diabetics, and delicious. This type of fasting does not place undue stress on the body as more extreme fasts can do. My theory is that palahar has its roots in ancient times when certain ascetics ate only what was available without human intervention via farming.

RG: What is the mindful practice around cooking and eating that you follow?

CTS: Because my husband is diabetic, we are very careful what we eat. We restrict our consumption of carbs and eat 5-7 servings of fruits and vegetables a day, very little red meat and a lot of fish and seafood.

RG: What is your enduring food memory while growing up?

CTS: My grandparents emigrated to Canada from England, so my mother cooked many traditional English dishes, such as minced meat pie, Irish stew, and sausage rolls. She was a great pastry maker. I still love these dishes. I think English food has an undeservedly bad reputation, perhaps because of bad cooks.

RG: What is a heritage cookware from that you possess and can’t part with? What is it associated with?

CTS: Mrs. Balbir Singh’s Indian Cookery, first published in 1961, is a classic. When my husband and I began cooking Indian food in the early 1970s, there wasn’t the abundance of cookbooks as today and Mrs. Singh was (and still is) our go-to book. It saved the day many years ago when we invited Nobel Laureate Subramaniam Chandrasekhar and his wife, both vegetarian, to dinner. We couldn’t serve them plain old dal and rice and turned to Mrs. Singh’s book for help. We found wonderful (and challenging) recipes for kamal kakri kofta, a lotus root ball curry, and navratan pulao, a multi-colored rice dish that Singh described as “a pullao amongst pullaos and a jewel amongst jewels.” The dinner was a great success.

RG: If you could invite anyone over for dinner, who would you call and what would you serve them?

CTS: I’m very interested in politics, so my first thought was to invite my husband’s former boss, President Bill Clinton, to dinner. He’s considered the most intelligent president in modern times and was known for his love of Indian food. But his heart attack led him to adopt a mainly vegan diet so that would limit our culinary possibilities. Instead, I’d invite Barack Obama and his wife Michelle in to hear their take on the current political scene in the US and abroad.

RG: What’s something you make a point of doing before any meal at which people gather around a table, and why do you do it?

CTS: I like to serve cocktails before a meal, especially an Indian meal. It’s my conviction that the best alcohol pairing — if one is going to serve alcohol — is a well-crafted cocktail made from carefully chosen ingredients. Those with a gin or rum base and various aromatic ingredients, including spices, can be excellent. With dinner, plain water is fine. I find pairing wine to be too much of a challenge.

Key Takeaways

- The Handbook is a superb guide to Indian cuisine.

- Sen on ancient India’s culinary medicine.

- Learn about multi-faith fasting traditions in India.